3. Symmetric Key Encryption

CPA Security

Secret keys are hard to manage and it would be efficient if we could use the same key multiple times. So we need a stronger notion of security, that the adversary is given several ciphertexts under the same key but the scheme is still secure.

We strengthen the adversary’s power, and assume that the adversary can obtain encryptions of any plaintext. This attack model is called chosen plaintext attack (CPA).

This notion can be formalized as a security game. The difference here is that we must guarantee security for multiple encryptions.

Definition. For a given cipher $\mathcal{E} = (E, D)$ defined over $(\mathcal{K}, \mathcal{M}, \mathcal{C})$ and given an adversary $\mathcal{A}$, define experiments 0 and 1.

Experiment $b$.

- The challenger fixes a key $k \leftarrow \mathcal{K}$.

- The adversary submits a sequence of queries to the challenger:

- The $i$-th query is a pair of messages $m _ {i, 0}, m _ {i, 1} \in \mathcal{M}$ of the same length.

- The challenger computes $c _ i = E(k, m _ {i, b})$ and sends $c _ i$ to the adversary.

- The adversary computes and outputs a bit $b’ \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace$.

Let $W _ b$ be the event that $\mathcal{A}$ outputs $1$ in experiment $b$. Then the CPA advantage with respect to $\mathcal{E}$ is defined as

\[\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{CPA}}[\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{E}] = \left\lvert \Pr[W _ 0] - \Pr[W _ 1] \right\lvert\]If the CPA advantage is negligible for all efficient adversaries $\mathcal{A}$, then the cipher $\mathcal{E}$ is semantically secure against chosen plaintext attack, or simply CPA secure.

The above security game is indeed a chosen plaintext attack since if the attacker sends two identical messages $(m, m)$ as a query, it can surely obtain an encryption of $m$.

The assumption that the adversary can choose any message of its choice may seem too strong, but there are cases in the real world. Also, cryptographers use strong models to show proof of security even for strong attackers.

Deterministic Cipher is not CPA Secure

Suppose that $E$ is deterministic. Then we can construct an adversary that breaks CPA security. For example, the adversary can send $(m _ 0, m _ 1)$ and $(m _ 0, m _ 2)$. Then if $b = 0$, the received ciphertext would be same, so the adversary can output $0$ and win the CPA security game.

Therefore, for indistinguishability under chosen plaintext attack (IND-CPA), encryption must produce different outputs even for the same plaintext.

Another corollary is that PRPs are deterministic, so PRPs are not CPA secure.

Nonce-based Encryption

Since deterministic cipher is not CPA secure, we need non-deterministic encryption. There are two ways to construct such encryptions.

In probabilistic (randomized) encryption, encrypting the same message twice gives difference ciphertexts with high probability.

The second method is stateful encryption, where both algorithms $E$ and $D$ maintain some state that changes with each invocation of the algorithm. A typical example of stateful encryption is nonce-based encryption.

A nonce is a value that changes from message to message, such as a counter or a random value. Both encryption and decryption algorithm take the nonce as an additional input, so that the resulting ciphertext will be different for the same plaintext. Thus, it is natural that we require all nonces to be distinct.

The syntax for nonce-based encryption is $c = E(k, m, n)$ where $n \in \mathcal{N}$ is the nonce, and the algorithm $E$ is required to be deterministic. Similarly, nonce-based decryption becomes $m = D(k, c, n)$. The nonce that was used to encrypt $m$ should be used for decrypting $c$.

We also formalize security for nonce-based encryption. It is basically the same as CPA security definition. The difference is that the adversary chooses a nonce for each query, with the constraint that they should be unique for every query.

Definition. For a given nonce-based cipher $\mathcal{E} = (E, D)$ defined over $(\mathcal{K}, \mathcal{M}, \mathcal{C}, \mathcal{N})$ and given an adversary $\mathcal{A}$, define experiments 0 and 1.

Experiment $b$.

- The challenger fixes a key $k \leftarrow \mathcal{K}$.

- The adversary submits a sequence of queries to the challenger.

- The $i$-th query is a pair of messages $m _ {i, 0}, m _ {i, 1} \in \mathcal{M}$ of the same length, and a nonce $n _ i \in \mathcal{N} \setminus \left\lbrace n _ 1, \dots, n _ {i-1} \right\rbrace$.

- Nonces should be unique.

- The challenger computes $c _ i = E(k, m _ {i, b}, n _ i)$ and sends $c _ i$ to the adversary.

- The adversary computes and outputs a bit $b’ \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace$.

Let $W _ b$ be the event that $\mathcal{A}$ outputs $1$ in experiment $b$. Then the CPA advantage with respect to $\mathcal{E}$ is defined as

\[\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{nCPA}}[\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{E}] = \left\lvert \Pr[W _ 0] - \Pr[W _ 1] \right\lvert\]If the CPA advantage is negligible for all efficient adversaries $\mathcal{A}$, then the nonce-based cipher $\mathcal{E}$ is semantically secure against chosen plaintext attack, or simply CPA secure.

Secure Construction from PRF

Suppose we want to construct a secure encryption scheme from a pseudorandom function. A simple approach would be to use $E(k, m) = F(k, m)$, but this would result in deterministic encryption, which is not CPA-secure.

Therefore, we need randomized encryption. We achieve randomness by drawing a random value $r \leftarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$ and evaluate $F(k, r)$ and then XOR it with the plaintext.

Here is the construction in detail.

Let $F : \mathcal{K} \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$ be a PRF.

- Encryption $E : \mathcal{K} \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{2n}$

- Sample $r \leftarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$ and return $c = (r, F(k, r) \oplus m)$.

- Decryption $D : \mathcal{K} \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{2n} \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$

- Extract $(r, s)$ from $c$ and output $m = F(k, r) \oplus s$.

A few notes:

- Since we have randomized encryption,

- $E$ is a one-to-many function.

- $D$ is a many-to-one function.

- The above construction maps $n$ bit messages to $2n$ bit messages.

- The ciphertext is $2$ times longer than the plaintext.

- We call this the expansion ratio.

- If the value $F(k, r)$ is duplicated in the above construction, then this scheme is insecure, just like in the one-time pad.

- Thus the probability of duplication must be negligible.

Since the duplication probability is negligible, we have the following theorem.

Theorem. Let $F$ be a secure PRF. Then $(E, D)$ in the above construction is CPA-secure.

Proof. Check the proof of Theorem 3.29.1

Notes on the Proof

There is a common proof template for constructions based on PRFs.

- Consider a hypothetical version of the construction, where the PRF is replaced by a truly random function.

- Argue that the adversary learns almost nothing. i.e, replacing with a random function only has a negligible effect on the adversary.

- Now that we have a random function, the remaining argument proceeds with probabilistic analysis, etc.

Modes of Operation

We learned how to encrypt a single block. How do we encrypt longer messages with a block cipher $E : \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^s \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n \rightarrow \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$?

There are many ways of processing multiple blocks, this is called the mode of operation.

Additional explanation available in Modes of Operations (Internet Security).

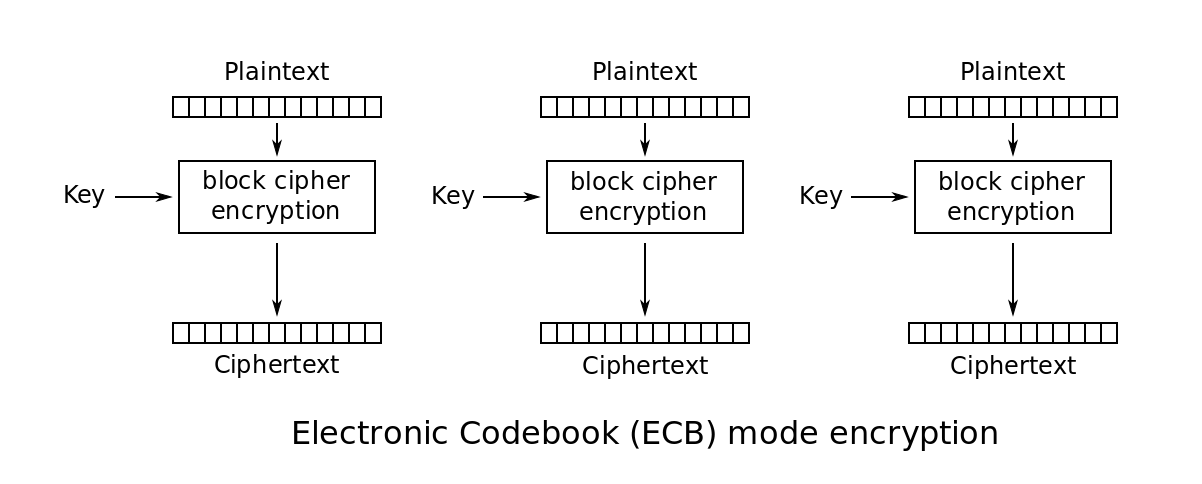

Electronic Codebook Mode (ECB)

- ECB mode encrypts each block with the same key.

- Blocks are independent of each other.

- ECB is deterministic, so not CPA-secure.

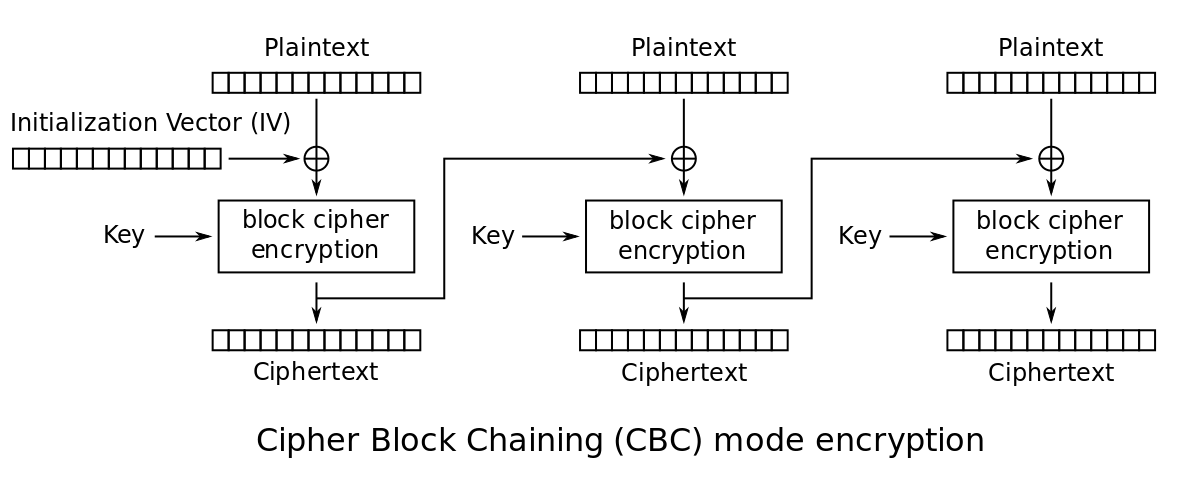

Ciphertext Block Chain Mode (CBC)

Let $X = \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^n$ and $E : \mathcal{K} \times X \rightarrow X$ be a PRP.

- In CBC mode, a random initial vector (IV) is chosen and outputs the ciphertext.

- Expansion ratio is $\frac{n+1}{n}$ where $n$ is the number of blocks.

- If the message size is not a multiple of the block size, we need padding.

There is a security proof for CBC mode.

Theorem. Let $E : \mathcal{K} \times X \rightarrow X$ be a secure PRP. Then CBC mode encryption $E : \mathcal{K} \times X^L \rightarrow X^{L+1}$ is CPA-secure for any $L > 0$.

For any $q$-query adversary $\mathcal{A}$, there exists a PRP adversary $\mathcal{B}$ such that

\[\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{CPA}}[\mathcal{A}, E] \leq 2 \cdot \mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{PRP}}[\mathcal{B}, E] + \frac{2q^2L^2}{\left\lvert X \right\lvert}.\]

Proof. See Theorem 5.4.2

From the above theorem, note that CBC is only secure as long as $q^2L^2 \ll \left\lvert X \right\lvert$.

Also, CBC mode is not secure if the adversary can predict the IV of the next message. Proceed as follows:

- Query the challenger for an encryption of $m _ 0$ and $m _ 1$.

- Receive $\mathrm{IV} _ 0, E(k, \mathrm{IV} _ 0 \oplus m _ 0)$ and $\mathrm{IV} _ 1, E(k, \mathrm{IV} _ 1 \oplus m _ 1)$.

Predict the next IV as $\mathrm{IV} _ 2$, and set the new query pair as

\[m _ 0' = \mathrm{IV} _ 2 \oplus \mathrm{IV} _ 0 \oplus m _ 0, \quad m _ 1' = \mathrm{IV} _ 2 \oplus \mathrm{IV} _ 1 \oplus m _ 1\]and send it to the challenger.

- In experiment $b$, the adversary will receive $E(k, \mathrm{IV} _ b \oplus m _ b)$. Compare this with the result of the query from (2). The adversary wins with advantage $1$.

(More on this to be added)

Nonce-based CBC Mode

We can also use a unique nonce to generate the IV. Specifically,

\[\mathrm{IV} = E(k _ 1, n)\]where $k _ 1$ is the new key and $n$ is a nonce. The ciphertext starts with $n$ instead of the $\mathrm{IV}$.

Note that if $k _ 1$ is the same as the key used for encrypting messages, then this scheme is insecure. See Exercise 5.14.2

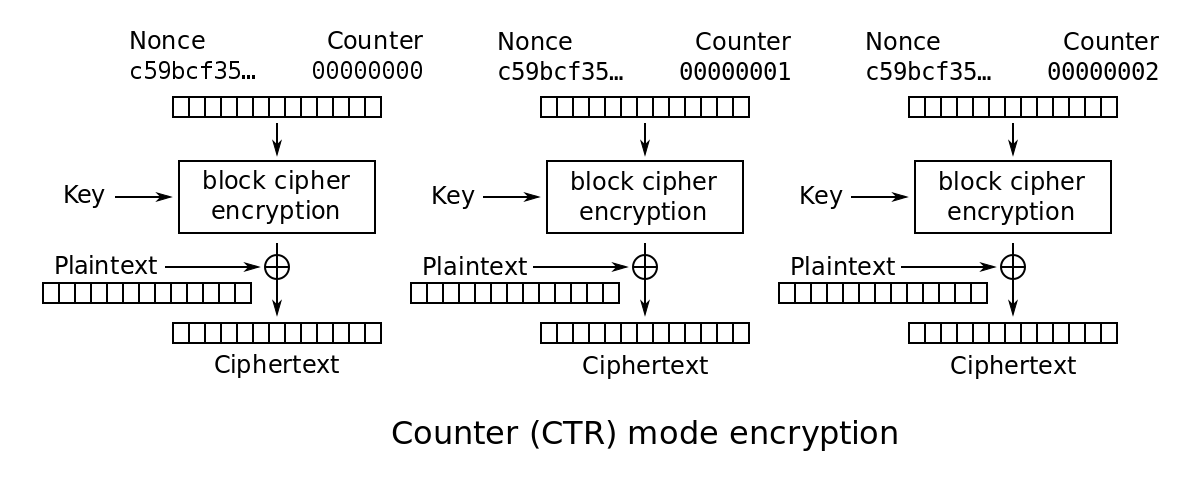

Counter Mode (CTR)

Let $F : \mathcal{K} \times X \rightarrow X$ be a secure PRF.

- CTR mode also chooses a random IV and increments the IV for every encrypted block.

- IVs should not be reused.

- CTR mode is parallelizable, so it is very efficient.

- If a part of the message changes, only that part has to be recalculated.

There is also a security proof for CTR mode.

Theorem. If $F : \mathcal{K} \times X \rightarrow X$ is a secure PRF, then CTR mode encryption $E : \mathcal{K} \times X^L \rightarrow X^{L+1}$ is CPA-secure.

For any $q$-query adversary $\mathcal{A}$ against $E$, there exists a PRF adversary $\mathcal{B}$ such that

\[\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{CPA}}[\mathcal{A}, E] \leq 2\cdot\mathrm{Adv} _ {\mathrm{PRF}}[\mathcal{B}, F] + \frac{4q^2L}{\left\lvert X \right\lvert}.\]

Proof. Refer to Theorem 5.3.2

From the above theorem, we see that CTR mode is only secure for $q^2L \ll \left\lvert X \right\lvert$. This is a better bound than CBC.

Nonce-based CTR Mode

We can also use a nonce and a counter to generate the IV. Since it is important to keep IVs distinct, set

\[\mathrm{IV} = (n, ctr) \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{64} \times \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace^{64}\]where $ctr$ starts at $0$ for every message and $n \in \mathcal{N}$ is chosen randomly as a nonce.

Comparison of CTR and CBC

CTR is a lot better in general, but CBC is widely implemented.

| - | CBC | CTR |

|---|---|---|

| Primitive | PRP | PRF |

| Parallelizable | No | Yes |

| Security | $q^2L^2 \ll \left\lvert X \right\lvert$ | $q^2L \ll \left\lvert X \right\lvert$ |

| Dummy Padding | Yes | No |

| 1-byte Message | $16 \times$ expansion | No expansion |

- PRP is a PRF, so PRF is a weaker condition.

- The difference of $q^2L^2$ and $q^2L$ comes from the probability that consecutive IVs overlap, and also the birthday paradox.

- CBC needs dummy padding block, but this can be avoided using ciphertext stealing. (See Exercise 5.16.2)

- CTR mode does not require padding by construction.