9. Public Key Encryption

In symmetric encryption, we assumed that the two parties had a shared key in advance. If the two parties do not have a shared key, public-key encryption can be used to encrypt messages.

Public Key Encryption

Definition. A public key encryption scheme $\mc{E} = (G, E, D)$ is a triple of efficient algorithms: a key generation algorithm $G$, an encryption algorithm $E$, a decryption algorithm $D$.

- $G$ generates a key pair as $(pk, sk) \la G()$. $pk$ is called a public key and $sk$ is called a secret key.

- $E$ takes a public key $pk$ and a message $m$ and outputs ciphertext $c \la E(pk, m)$.

- $D$ takes a secret key $sk$ and a ciphertext $c$ and outputs plaintext $m \la D(sk, c)$ or a special $\texttt{reject}$ value $\bot$.

We say that $\mc{E} = (G, E, D)$ is defined over $(\mc{M}, \mc{C})$.

$G$ and $E$ may be probabilistic, but $D$ must be deterministic. Also, correctness condition is required. For any $(pk, sk)$ and $m \in \mc{M}$,

\[\Pr[D(sk, E(pk, m)) = m] = 1.\]Public key $pk$ will be publicized. After Alice obtains $pk$, she can use it to encrypt any message and send it to Bob. This is the only interaction required. The public key can be used multiple times, and others besides Alice can use it too. Finally, $sk$ should be hard to compute from $pk$, obviously for security.

CPA Security for Public Key Encryption

Semantic Security

The following notion of security is only for an eavesdropping adversary.

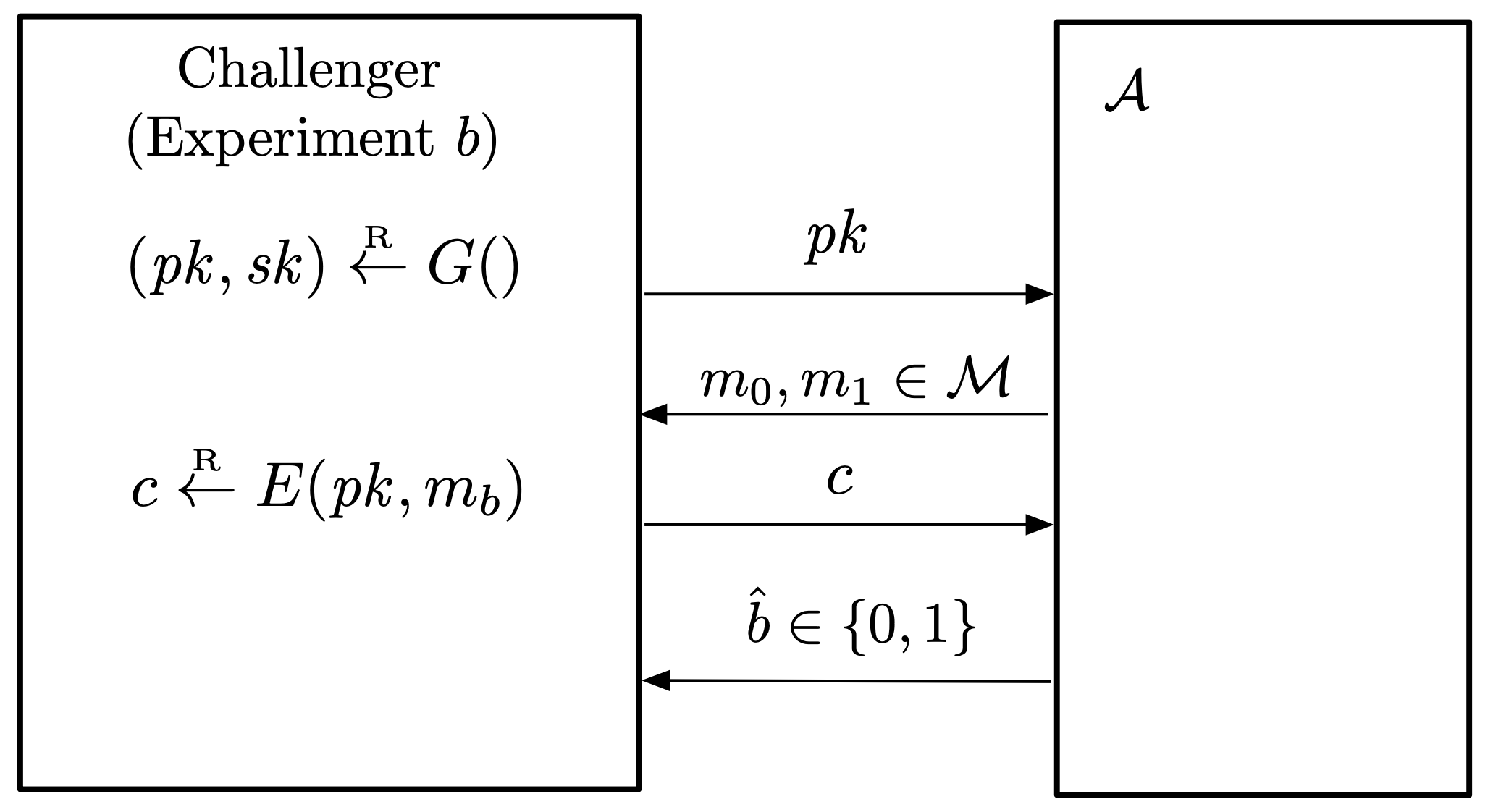

Definition. Let $\mc{E} = (G, E, D)$ be a public key encryption scheme defined over $(\mc{M}, \mc{C})$. For an adversary $\mc{A}$, we define two experiments.

Experiment $b$.

- The challenger computes $(pk, sk) \la G()$ and sends $pk$ to the adversary.

- The adversary chooses $m _ 0, m _ 1 \in \mc{M}$ of the same length, and sends them to the challenger.

- The challenger computes $c \la E(pk, m _ b)$ and sends $c$ to the adversary.

- $\mc{A}$ outputs a bit $b’ \in \braces{0, 1}$.

Let $W _ b$ be the event that $\mc{A}$ outputs $1$ in experiment $b$. The advantage of $\mc{A}$ with respect to $\mc{E}$ is defined as

\[\Adv[SS]{\mc{A}, \mc{E}} = \abs{\Pr[W _ 0] - \Pr[W _ 1]}.\]$\mc{E}$ is semantically secure if $\rm{Adv} _ {\rm{SS}}[\mc{A}, \mc{E}]$ is negligible for any efficient $\mc{A}$.

Note that $pk$ is sent to the adversary, and adversary can encrypt any message! Thus, encryption must be randomized. Otherwise, the adversary can compute $E(pk, m _ b)$ for each $b$ and compare with $c$ given from the challenger.

Semantic Security $\implies$ CPA

For symmetric ciphers, semantic security (one-time) did not guarantee CPA security (many-time). But in public key encryption, semantic security implies CPA security. This is because the attacker can encrypt any message using the public key.

First, we check the definition of CPA security for public key encryption. It is similar to that of symmetric ciphers, compare with CPA Security for symmetric key encryption (Modern Cryptography).

Definition. For a given public-key encryption scheme $\mc{E} = (G, E, D)$ defined over $(\mc{M}, \mc{C})$ and given an adversary $\mc{A}$, define experiments 0 and 1.

Experiment $b$.

- The challenger computes $(pk, sk) \la G()$ and sends $pk$ to the adversary.

- The adversary submits a sequence of queries to the challenger:

- The $i$-th query is a pair of messages $m _ {i, 0}, m _ {i, 1} \in \mc{M}$ of the same length.

- The challenger computes $c _ i = E(pk, m _ {i, b})$ and sends $c _ i$ to the adversary.

- The adversary computes and outputs a bit $b’ \in \braces{0, 1}$.

Let $W _ b$ be the event that $\mc{A}$ outputs $1$ in experiment $b$. Then the CPA advantage with respect to $\mc{E}$ is defined as

\[\Adv[CPA]{\mc{A}, \mc{E}} = \abs{\Pr[W _ 0] - \Pr[W _ 1]}.\]If the CPA advantage is negligible for all efficient adversaries $\mc{A}$, then $\mc{E}$ is semantically secure against chosen plaintext attack, or simply CPA secure.

We formally prove the following theorem.

Theorem. If a public-key encryption scheme $\mc{E}$ is semantically secure, then it is also CPA secure.

For any $q$-query CPA adversary $\mc{A}$, there exists an SS adversary $\mc{B}$ such that

\[\rm{Adv} _ {\rm{CPA}}[\mc{A}, \mc{E}] = q \cdot \rm{Adv} _ {\rm{SS}}[\mc{B}, \mc{E}].\]

Proof. The proof uses a hybrid argument. For $j = 0, \dots, q$, the hybrid game $j$ is played between $\mc{A}$ and a challenger that responds to the $q$ queries as follows:

- On the $i$-th query $(m _ {i,0}, m _ {i, 1})$, respond with $c _ i$ where

- $c _ i \la E(pk, m _ {i, 1})$ if $i \leq j$.

- $c _ i \la E(pk, m _ {i, 0})$ otherwise.

So, the challenger in hybrid game $j$ encrypts $m _ {i, 1}$ in the first $j$ queries, and encrypts $m _ {i, 0}$ for the rest of the queries. If we define $p _ j$ to be the probability that $\mc{A}$ outputs $1$ in hybrid game $j$, we have

\[\Adv[CPA]{\mc{A}, \mc{E}} = \abs{p _ q - p _ 0}\]since hybrid $q$ is precisely experiment $1$, hybrid $0$ is experiment $0$. With $\mc{A}$, we define $\mc{B}$ as follows.

- $\mc{B}$ randomly chooses $\omega \la \braces{1, \dots, q}$.

- $\mc{B}$ obtains $pk$ from the challenger, and forwards it to $\mc{A}$.

- For the $i$-th query $(m _ {i, 0}, m _ {i, 1})$ from $\mc{A}$, $\mc{B}$ responds as follows.

- If $i < \omega$, $c \la E(pk, m _ {i, 1})$.

- If $i = \omega$, forward query to the challenger and forward its response to $\mc{A}$.

- Otherwise, $c _ i \la E(pk, m _ {i, 0})$.

- $\mc{B}$ outputs whatever $\mc{A}$ outputs.

Note that $\mc{B}$ can encrypt queries on its own, since the public key is given. Define $W _ b$ as the event that $\mc{B}$ outputs $1$ in experiment $b$ in the semantic security game. For $j = 1, \dots, q$, we have that

\[\Pr[W _ 0 \mid \omega = j] = p _ {j - 1}, \quad \Pr[W _ 1 \mid \omega = j] = p _ j.\]In experiment $0$ with $\omega = j$, $\mc{A}$ receives encryptions of $m _ {i, 1}$ in the first $j - 1$ queries and receives encryptions of $m _ {i, 1}$ for the rest of the queries. The second equation follows similarly.

Then the SS advantage can be calculated as

\[\begin{aligned} \Adv[SS]{\mc{B}, \mc{E}} &= \abs{\Pr[W _ 0] - \Pr[W _ 1]} \\ &= \frac{1}{q} \abs{\sum _ {j=1}^q \Pr[W _ 0 \mid \omega = j] - \sum _ {j = 1}^q \Pr[W _ 1 \mid \omega = j]} \\ &= \frac{1}{q} \abs{\sum _ {j=1}^q (p _ {j-1} - p _ j)} \\ &= \frac{1}{q} \Adv[CPA]{\mc{A}, \mc{E}}. \end{aligned}\]CCA Security for Public Key Encryption

We also define CCA security for public key encryption, which models a wide spectrum of real-world attacks. The definition is also very similar to that of symmetric ciphers, compare with CCA security for symmetric ciphers (Modern Cryptography).

Definition. Let $\mc{E} = (G, E, D)$ be a public-key encryption scheme over $(\mc{M}, \mc{C})$. Given an adversary $\mc{A}$, define experiments $0$ and $1$.

Experiment $b$.

- The challenger computes $(pk, sk) \la G()$ and sends $pk$ to the adversary.

- $\mc{A}$ makes a series of queries to the challenger, which is one of the following two types.

- Encryption: Send $(m _ {i _ ,0}, m _ {i, 1})$ and receive $c’ _ i \la E(pk, m _ {i, b})$.

- Decryption: Send $c _ i$ and receive $m’ _ i \la D(sk, c _ i)$.

- Note that $\mc{A}$ is not allowed to make a decryption query for any $c _ i’$.

- $\mc{A}$ outputs a pair of messages $(m _ 0^\ast , m _ 1^\ast)$.

- The challenger generates $c^\ast \la E(pk, m _ b^\ast)$ and gives it to $\mc{A}$.

- $\mc{A}$ is allowed to keep making queries, but not allowed to make a decryption query for $c^\ast$.

- The adversary computes and outputs a bit $b’ \in \left\lbrace 0, 1 \right\rbrace$.

Let $W _ b$ be the event that $\mc{A}$ outputs $1$ in experiment $b$. Then the CCA advantage with respect to $\mc{E}$ is defined as

\[\rm{Adv} _ {\rm{CCA}}[\mc{A}, \mc{E}] = \left\lvert \Pr[W _ 0] - \Pr[W _ 1] \right\lvert.\]If the CCA advantage is negligible for all efficient adversaries $\mc{A}$, then $\mc{E}$ is semantically secure against a chosen ciphertext attack, or simply CCA secure.

Note that encryption queries are not strictly required, since in public-key schemes, the adversary can encrypt any messages on its own. We can consider a restricted security game, where an adversary makes only a single encryption query.

Definition. If $\mc{A}$ is restricted to making a single encryption query, we denote its advantage by $\Adv[1CCA]{\mc{A}, \mc{E}}$. A public-key encryption scheme $\mc{E}$ is one-time semantically secure against chosen ciphertext attack, or simply 1CCA secure if $\Adv[1CCA]{\mc{A}, \mc{E}}$ is negligible for all efficient adversaries $\mc{A}$.

Similarly, 1CCA security implies CCA security, as in the above theorem. So to show CCA security for public-key schemes, it suffices to show that the scheme is 1CCA secure.

Theorem. If a public-key encryption scheme $\mc{E}$ is 1CCA secure, then it is also CCA secure.

Proof. Same as the proof in above theorem.

Active Adversaries in Symmetric vs Public Key

In symmetric key encryption, we studied authenticated encryption (AE), which required the scheme to be CPA secure and provide ciphertext integrity. In symmetric key settings, AE implied CCA.

However in public-key schemes, adversaries can always create new ciphertexts using the public key, which makes the original definition of ciphertext integrity unusable. Thus we directly require CCA security.

Hybrid Encryption and Key Encapsulation Mechanism

Symmetric key encryptions are significantly faster than public key encryption, so we use public-key encryption for sharing the key, and then the key is used for symmetric key encryption.

Generate $(pk, sk)$ for the public key encryption, and generate a symmetric key $k$. For the message $m$, encrypt it as

\[(c, c _ S) \la \big( E(pk, k), E _ S(k, m) \big)\]where $E _ S$ is the symmetric encryption algorithm, $E$ is the public-key encryption algorithm. The receiver decrypts $c$ and recovers $k$ that can be used for decrypting $c _ S$. This is a form of hybrid encryption. We are encapsulating the key $k$ inside a ciphertext, so we call this key encapsulation mechanism (KEM).

We can use public-key schemes for KEM, but there are dedicated constructions for KEM which are more efficient. The dedicated algorithms does the key generation and encryption in one-shot.

Definition. A KEM $\mc{E} _ \rm{KEM}$ consists of a triple of algorithms $(G, E _ \rm{KEM}, D _ \rm{KEM})$.

- The key generation algorithm generates $(pk, sk) \la G()$.

- The encapsulation algorithm generates $(k, c _ \rm{KEM}) \la E _ \rm{KEM}(pk)$.

- The decapsulation algorithm generates $k \la D _ \rm{KEM}(sk, c _ \rm{KEM})$.

Note that $E _ \rm{KEM}$ only takes the public key as a parameter. The correctness condition is that for any $(pk, sk) \la G()$ and any $(k, c _ \rm{KEM}) \la E _ \rm{KEM}(pk)$, we must have $k \la D _ \rm{KEM}(sk, c _ \rm{KEM})$.

Using the KEM, the symmetric key is automatically encapsulated during encryption process.

Definition. A KEM scheme is secure if any efficient adversary cannot distinguish between $(c _ \rm{KEM}, k _ 0)$ and $(c _ \rm{KEM}, k _ 1)$, where $k _ 0$ is generated by $E(pk)$, and $k _ 1$ is chosen randomly from $\mc{K}$.

Read more about this in Exercise 11.9.1

The ElGamal Encryption

We introduce a public-key encryption scheme based on the hardness of discrete logarithms.

Definition. Suppose we have two parties Alice and Bob. Let $G = \left\langle g \right\rangle$ be a cyclic group of prime order $q$, let $\mc{E} _ S = (E _ S, D _ S)$ be a symmetric cipher.

- Alice chooses $sk = \alpha \la \Z _ q$, computes $pk = g^\alpha$ and sends $pk$ to Bob.

- Bob also chooses $\beta \la \Z _ q$ and computes $k = h^\beta = g^{\alpha\beta}$.

- Bob sends $\big( g^\beta, E _ S(k, m) \big)$ to Alice.

- Alice computes $k = g^{\alpha\beta} = (g^\beta)^\alpha$ using $\alpha$ and recovers $m$ by decrypting $E _ S(k, m)$.

As a concrete example, set $E _ S(k, m) = k \cdot m$ and $D _ S(k, c) = k^{-1} \cdot c$. The correctness property automatically holds. Therefore,

- $G$ outputs $sk = \alpha \la \Z _ q$, $pk = h = g^\alpha$.

- $E(pk, m) = (c _ 1, c _ 2) \la (g^\beta, h^\beta \cdot m)$ where $\beta \la \Z _ q$.

- $D(sk, c) = c _ 2 \cdot (c _ 1)^{-\alpha} = m$.

Security of ElGamal Encryption

Theorem. If the DDH assumption holds on $G$, and the symmetric cipher $\mc{E} _ S = (E _ S, D _ S)$ is semantically secure, then the ElGamal encryption scheme $\mc{E} _ \rm{EG}$ is semantically secure.

For any SS adversary $\mc{A}$ of $\mc{E} _ \rm{EG}$, there exist a DDH adversary $\mc{B}$, and an SS adversary $\mc{C}$ for $\mc{E} _ S$ such that

\[\Adv[SS]{\mc{A}, \mc{E} _ \rm{EG}} \leq 2 \cdot \Adv[DDH]{\mc{B}, G} + \Adv[SS]{\mc{C}, \mc{E} _ S}.\]

Proof Idea. For any $m _ 0, m _ 1 \in G$ and random $\gamma \la \Z _ q$,

\[E _ S(g^{\alpha\beta}, m _ 0) \approx _ c E _ S(g^{\gamma}, m _ 0) \approx _ c E _ S(g^\gamma, m _ 1) \approx _ c E _ S(g^{\alpha\beta}, m _ 1).\]The first two and last two ciphertexts are computationally indistinguishable since the DDH problem is hard. The second and third ciphertexts are also indistinguishable since $\mc{E} _ S$ is semantically secure.

Proof. Full proof in Theorem 11.5.1

Note that $\beta \la \Z _ q$ must be chosen differently for each encrypted message. This is the randomness part of the encryption, since $pk = g^\alpha, sk =\alpha$ are fixed.

Hashed ElGamal Encryption

Hashed ElGamal encryption scheme is a variant of the original ElGamal scheme, where we use a hash function $H : G \ra \mc{K}$, where $\mc{K}$ is the key space of $\mc{E} _ S$.

The only difference is that we use $H(g^{\alpha\beta})$ as the key.2

- Alice chooses $sk = \alpha \la \Z _ q$, computes $pk = g^\alpha$ and sends $pk$ to Bob.

- Bob also chooses $\beta \la \Z _ q$ and computes $h^\beta = g^{\alpha\beta}$, and sets $k = H(g^{\alpha\beta})$.

- Bob sends $\big( g^\beta, E _ S(k, m) \big)$ to Alice.

- Alice computes $g^{\alpha\beta} = (g^\beta)^\alpha$ using $\alpha$, computes $k = H(g^{\alpha\beta})$ and recovers $m$ by decrypting $E _ S(k, m)$.

This is also semantically secure, under the random oracle model.

Theorem. Let $H : G \ra \mc{K}$ be modeled as a random oracle. If the CDH assumption holds on $G$ and $\mc{E} _ S$ is semantically secure, then the hashed ElGamal scheme $\mc{E} _ \rm{HEG}$ is semantically secure.

Proof Idea. Given a ciphertext $\big( g^\beta, E _ S(k, m) \big)$ with $k = H(g^{\alpha\beta})$, the adversary learns nothing about $k$ unless it constructs $g^{\alpha\beta}$. This is because we modeled $H$ as a random oracle. If the adversary learns about $k$, then this adversary breaks the CDH assumption for $G$. Thus, if CDH assumption holds for the adversary, $k$ is completely random, so the hashed ElGamal scheme is secure by the semantic security of $\mc{E} _ S$.

Proof. Refer to Theorem 11.4.1

Since the hashed ElGamal scheme is semantically secure, it is automatically CPA secure. But this is not CCA secure, and we need a stronger assumption.

Interactive Computational Diffie-Hellman Problem (ICDH)

Definition. Let $G = \left\langle g \right\rangle$ be a cyclic group of prime order $q$. Let $\mc{A}$ be a given adversary.

- The challenger chooses $\alpha, \beta \la \Z _ q$ and sends $g^\alpha, g^\beta$ to the adversary.

- The adversary makes a sequence of DH-decision oracle queries to the challenger.

- Each query has the form $(v, w) \in G^2$, challenger replies with $1$ if $v^\alpha = w$, replies $0$ otherwise.

- The adversary calculates and outputs some $w \in G$.

We define the advantage in solving the interactive computational Diffie-Hellman problem for $G$ as

\[\Adv[ICDH]{\mc{A}, G} = \Pr[w = g^{\alpha\beta}].\]We say that the interactive computational Diffie-Hellman (ICDH) assumption holds for $G$ if for any efficient adversary $\mc{A}$, $\Adv[ICDH]{\mc{A}, G}$ is negligible.

This is also known as gap-CDH. Intuitively, it says that even if we have a DDH solver, CDH is still hard.

CCA Security of Hashed ElGamal

Theorem. If the gap-CDH assumption holds on $G$ and $\mc{E} _ S$ provides AE and $H : G \ra \mc{K}$ is a random oracle, then the hashed ElGamal scheme is CCA secure.

Proof. See Theorem 12.4.1 (very long)

The RSA Encryption

The RSA scheme was originally designed by Rivest, Shamir and Adleman in 1977.3 The RSA trapdoor permutation is used in many places such as SSL/TLS, both for encryption and digital signatures.

Textbook RSA Encryption

The “textbook RSA” is done as follows.

- Key generation algorithm $G$ outputs $(pk, sk)$.

- Sample two large random primes $p, q$ and set $N = pq$.

- Choose $e \in \Z$ such that $\gcd(e, \phi(N)) = 1$, compute $d = e^{-1} \bmod{\phi(N)}$.

- Output $pk = (N, e)$, $sk = (N, d)$.

- Encryption $E(pk, m) = m^e \bmod N$.

- Decryption $D(sk, c) = c^d \bmod N$ .

Correctness holds by Fermat’s little theorem. $ed = 1 \bmod \phi(N)$, so

\[D(sk, (E(pk, m))) = m^{ed} = m^{1 + k(p-1)(q-1)} \bmod N.\]Since $m^{p-1} = 1 \bmod p$, $m^{ed} = m \bmod N$ (holds trivially if $p \mid m$). A similar argument holds for modulus $q$, so we have $m^{ed} = m \bmod N$.

Attacks on Textbook RSA Encryption

But this scheme is not CPA secure, since it is deterministic and the ciphertext is malleable. For instance, one can choose two messages to be $1$ and $2$. Then the ciphertext is easily distinguishable.

Also, ciphertext is malleable by the homomorphic property. If $c _ 1 = m _ 1^e \bmod N$ and $c _ 2 = m _ 2^e \bmod N$, then set $c =c _ 1c _ 2 = (m _ 1m _ 2)^e \bmod N$, which is an encryption of $m _ 1m _ 2$.

Attack on KEM

Assume that the textbook RSA is used as KEM. Suppose that $k$ is $128$ bits, and the attacker sees $c = k^e \bmod N$. With high probability ($80\%$), $k = k _ 1 \cdot k _ 2$ for some $k _ 1, k _ 2 < 2^{64}$. Using the homomorphic property, $c = k _ 1^e k _ 2^e \bmod N$, so the following attack is possible.

- Build a table of $c\cdot k _ 2^{-e}$ for $0 \leq k _ 2 < 2^{64}$.

- For each $1 \leq k _ 1 < 2^{64}$, compute $k _ 1^e$ to check if it is in the table.

- Output a match $(k _ 1, k _ 2)$.

The attack has complexity $\mc{O}(2^{n/2})$ where $n$ is the key length.

Trapdoor Functions

Textbook RSA is not secure, but it is a one-way trapdoor function.

A one-way function is a function that is computationally hard to invert. But we sometimes need to invert the functions, so we need functions that have a trapdoor. A trapdoor is a secret door that allows efficient inversion, but without the trapdoor, the function must be still hard to invert.

Definition. Let $\mc{X}$ and $\mc{Y}$ be finite sets. A trapdoor function scheme $\mc{T} = (G, F, I)$ defined over $(\mc{X}, \mc{Y})$ is a triple of algorithms.

- $G$ is a probabilistic key generation algorithm that outputs $(pk, sk)$, where $pk$ is the public key and $sk$ is the secret key.

- $F$ is a deterministic algorithm that outputs $y \la F(pk, x)$ for $x \in \mc{X}$.

- $I$ is a deterministic algorithm that outputs $x \la I(sk, y)$ for $y \in \mc{Y}$.

The correctness property says that for any $(pk, sk) \la G()$ and $x \in \mc{X}$, $I(sk, F(pk, x)) = x$. So $sk$ is the trapdoor that inverts this function.

One-wayness is defined as a security game.

Definition. Given a trapdoor function scheme $\mc{T} = (G, F, I)$ and an adversary $\mc{A}$, define a security game as follows.

- The challenger computes $(pk, sk) \la G()$, $x \la \mc{X}$ and $y \la F(pk, x)$.

- The challenger sends $pk$ and $y$ to the adversary.

- The adversary computes and outputs $x’ \in \mc{X}$.

$\mc{A}$ wins if $\mc{A}$ inverts the function. The advantage is defined as

\[\Adv[OW]{\mc{A}, \mc{T}} = \Pr[x = x'].\]If the advantage is negligible for any efficient adversary $\mc{A}$, then $\mc{T}$ is one-way.

A one-way trapdoor function is not an encryption. The algorithm is deterministic, so it is not CPA secure. Never encrypt with trapdoor functions.

Textbook RSA as a Trapdoor Function

It is easy to see that the textbook RSA is a trapdoor function.

- Key generation algorithm $G$ chooses random primes $p, q$ and sets $N = pq$.

- Then chooses integer $e$ such that $\gcd(e, \phi(N)) = 1$.

- Set $d = e^{-1} \bmod \phi(N)$.

- Then $F(pk, x) = x^e \bmod N$, and $I(sk, y) = y^d \bmod N$.

- The correctness property holds by the above proof.

But is RSA a secure trapdoor function? Is it one-way?

- If $d$ is known, it is obviously not one-way.

- If $\phi(N)$ is known, it is not one-way.

- One can find $d = e^{-1} \bmod \phi(N)$.

- If $p$ and $q$ are known, it is not one-way.

- $\phi(N) = (p-1)(q-1)$.

Thus, if factoring is easy, RSA is not one-way. Thus if RSA is a secure trapdoor function, then factoring must be hard. How about the converse? We don’t have a proof, but it seems reasonable to assume.

The RSA Assumption

The RSA assumption says that the RSA problem is hard, which implies that RSA is a one-way trapdoor function.

The RSA Problem

Definition. Let $\mc{T} _ \rm{RSA} = (G, F, I)$ the RSA trapdoor function scheme. Given an adversary $\mc{A}$,

- The challenger chooses $(pk, sk) \la G()$ and $x \la \Z _ N$.

- $pk = (N, e)$, $sk = (N, d)$.

- The challenger computes $y \la x^e \bmod N$ and sends $pk$ and $y$ to the adversary.

- The adversary computes and outputs $x’ \in \Z _ N$.

The adversary wins if $x = x’$. The advantage is defined as

\[\rm{Adv} _ {\rm{RSA}}[\mc{A}, \mc{T _ \rm{RSA}}] = \Pr[x = x'].\]We say that the RSA assumption holds if the advantage is negligible for any efficient $\mc{A}$.

RSA Public Key Encryption (ISO Standard)

- Let $(E _ S, D _ S)$ be a symmetric encryption scheme over $(\mc{K}, \mc{M}, \mc{C})$ that provides AE.

- Let $H : \Z _ N^{\ast} \ra \mc{K}$ be a hash function.

The RSA public key encryption is done as follows.

- Key generation is the same.

- Encryption

- Choose random $x \la \Z _ N^{\ast}$ and let $y = x^e \bmod N$.

- Compute $c \la E _ S(H(x), m)$.

- Output $c’ = (y, c)$.

- Decryption

- Output $D _ S(H(y^d), c)$.

This works because $x = y^d \bmod N$ and $H(y^d) = H(x)$. In short, this uses RSA trapdoor function as a key exchange mechanism, and the actual encryption is done by symmetric encryption.

It is known that with RSA assumption and $H$ modeled as a random oracle, this scheme is CPA secure.

Optimizations for RSA

The computation time depends on the exponents $e, d$.

- To speed up RSA, choose a small public exponent $e$.

- $e = 65537 = 2^{16} + 1$ is often used, which only takes $17$ multiplications.

- But $d$ cannot be too small.

- RSA is insecure for $d < N^{0.25}$. (Wiener’87)

- RSA is insecure for $d < N^{0.292}$. (BD’98)

- Is RSA secure for $d < N^{0.5}$? (open problem)

- Often, encryption is fast, but decryption is slow.

- ElGamal takes approximately the same time for both.4

Attacks on RSA Implementation

- Timing Attack

- Time to compute $c^d \bmod N$ exposes $d$.

- More $1$’s in the binary representation of $d$ leads to more multiplications.

- Power Attack

- The power consumption of a smartcard during the computation of $c^d \bmod N$ exposes $d$.

- Faults Attack

- An error during computation exposes $d$.

- Poor Randomness

- Poor entropy at initialization, then same $p$ is generated for multiple devices.

- Collect modulus $N$ from many public keys, and their $\gcd$ will be $p$.

- PRG must be properly seeded when generating keys.

There is another variant that uses $H : G^2 \ra \mc{K}$ and sets $H(g^\beta, g^{\alpha\beta})$ as the key. This one is also semantically secure, and gives further security properties than the one in the text. ↩︎

This was one year before ElGamal. ↩︎

Discrete logarithms have the same complexity for average case and worst case, but this is not the case for RSA. (Source?) ↩︎